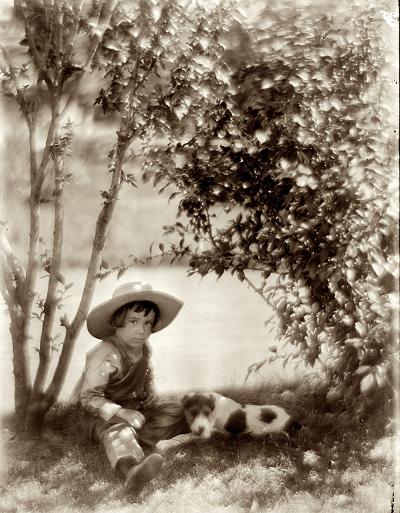

Another Shorpy photo – this one "Boy with Dog", Long Island 1904.

Another Shorpy photo – this one "Boy with Dog", Long Island 1904.

Why is it, I wonder, that we react so differently to a photograph like this than to a painting. Just a boy and his dog posing momentarily, not giving it much of a thought, yet here we are, over 100 years later, looking at that moment caught in time, and we inevitably think about that, about the passing time, about the fact that boy, dog and photographer are all dead, and like all old photos it acquires that poignancy; time interrupted, then restarted. A memento to mortality. Little did they know, we think to ourselves, what fate had in store. How innocent; how human.

Yet a painting of a boy and a dog, no matter how realistic, entirely fails – for me, at any rate – to conjure up anything like such thoughts. My chief point of attention will be the aesthetics of the piece, and the skill of the painter. I may vaguely wonder about the lives of the subjects, I suppose, but not with the same immediacy that I would with a photograph: no more than if I was reading about them. Some Reynolds portrait, say, of the son of Lord Somebody, with his pet dog: the fact that the child actually existed at that time, posed for hours in front of Sir Joshua, then grew up (or maybe didn't) and then died, is something I'm clearly aware of, but these are facts with no emotional content. Maybe, you might think, if the portrait was powerful enough you'd get that emotional content: but that's a different kind of feeling, I think, more to do with the character of the sitter and the skill of the portraitist.

Is that just because photography's a newer art form? That we're more used to paintings, and so have lost that sense of the power of a portrait that perhaps our forebears felt? In which case we should expect our descendants, in a few hundred years time, when photos of people who died centuries before will be utterly commonplace, to have lost that feeling of…of what? Sadness? Poignancy is the word I've used, and I don't know how else to describe it.

It's plausible, I suppose, but there seems to be more to it than that: something about the reality of it, even if, as sophisticates, we've been told not to rely too much on that naive trust in what's real and what isn't. We still see a person – not a portrait, a person – looking back at us from the distant past, and we get some kind of shiver, some intimation of mortality.

Leave a comment